India Travel Journal

29 December 2005 – 12 January 2006

Peter Hulen

I - American 293 Chicago to New Delhi

Night has fallen. The flight is

completely full and we

are already late departing, but not by a lot. This is a direct flight

from Chicago to New Delhi, and about fifteen hours, total.

There was a well-dressed couple in the

check-in line going home to

Mexico City. They had four huge suitcases and assorted carry-ons. The

woman was very friendly, looked at our shoulder bags and asked, “Is

that all you are taking to India?” When we said yes, she did a double

take at our bags and asked, “So, are going to do some meditating?” I

guess she thought if we had so few belongings we must be some kind of

ascetics or something.

Jenny and I sat in the food court on our end of the concourse and

watched people

and ate panini. She got a better idea of how salwar kamiz, sweaters

and dupatta are combined by

looking at the way

some Indian women were dressed.

II - Over the Aral Sea

It has been night all the way. We have about three hours to go, and

everyone is looking

pretty rough. I sure feel worse than I expected.

III - Room 201,

Jukaso Inn, New Delhi

We landed in New Delhi sometime before midnight and went through

customs very quickly. As we were all

getting our carry-ons down from the overheads, one man—a

cheerful, turbaned Sikh—said

his bag was so heavy because he had thirty

pounds of chocolate in it for his eight nieces and nephews.

The streets were very dimly lit,

and with a few exceptions no business signs were lit. As far as I could

tell, street signs are non-existent except on major thoroughfares.

We went down what we thought was the Main Bazaar in Paharganj looking

for either our hotel or one of the others the book listed just

to get our bearings. It was dark, the street was littered with

trash, and there were lots of people just hanging around. This was

around midnight, and it was impossible to see any of the

unlit signs on the buildings. Turns out I was able to identify a hotel

in the book, and found out we were on a completely different street

than the one we wanted to be on.

We had seen a cow wandering around in a dark street around the corner

where the street we were on ended, so that was fun. I ended up giving

the taxi driver directions to the right street by following our

guidebook, but no sooner had we identified the first couple of hotels

than Jenny said, “I don’t want to stay here”.

IV - Back in Room

201 (continued)

Our second choice was in

Connaught Place, but again, the streets and fronts of the buildings

were dark and we could not find the hotel. Finally the taxi driver said

he would take us to a hotel “in

the Connaught

Place area.” He quoted a reasonable price, but ended up driving us

all the way over to Karol Bagh. The room was reasonable enough, and

after a transcontinental flight and all the stimulus, we could barely

stand

up, so we tipped the driver extra for his trouble and checked in.

Midrange hotels and other places in the industrializing

world can be very

photogenic, but the live experience often leaves many details to be

desired. I would have taken a photo of the room—an un-booked suite that

they gave us for the price of a regular double room—but its real, live

funkiness would have been lost.

We both knew it would all look better in the morning,

that we would rally, get the train tickets booked, find a hotel in the

right

area at the right price, fulfill our objectives for the day, and fill

up with some good food. In the meantime we would have to suffer through

the dark, strange, too-exhausted-to-sleep night that lay ahead of us.

I was so sleep-deprived and jetlagged by then that I could only

alternate an hour of sleep with an hour of lying perfectly still and

relaxed with my eyes closed and my mind racing. But we did settle in

fairly comfortably and get through the night in that manner.

And yes, things did look better in the

morning.

V - Room 201,

waiting for room service

Room service! But still funky and cheap and cool. All Indian food.

We were rested some this morning. As it began to get light I stumbled

to the bathroom to plug in the geyser—a kind of wall-mounted,

electric, on-demand water heater found in many mid-priced hotels

outside the U.S. None of its various indicator lights came on, but it

started making little, reassuring “something is happening inside me”

noises. I crawled back into bed.

After it got lighter we both got up. The hot water was hot as hell and

it felt good to bathe and shave in it. That was refreshing and

encouraging. The sun began to peep through the smog and it looked like

a nice day. I turned on some Indian classical musicians on the

television while we got ready and organized. The room did look better

by the light of day. We did not have a plan for breakfast, so we just

munched on a bag of beef jerky Jenny had bought and stored in her bag

before we left. That is pretty pathetic, but we knew there were better

things to come.

The buildings across the street had that faded whitewash,

concrete-with-balconies, para-industrialized

adventure-land look. We could

smell food cooking somewhere through the open window, and spotted a

rooftop eatery across the way that started playing loud, thumping music

as some young men gathered there. A flock of green parrots flew in and

perched in a tall tree across the street. All in all, we felt refreshed

and ready for the day.

The same guy who had checked us in the night before was as the desk,

and he was friendly and cheerful. When we checked out, we were quoted

the same tariff promised the night before, and he called for a car to

take us wherever we were going next free of charge, also as promised.

The driver was a young, tall, good-looking guy who said his wife was a

cardiologist in Baltimore. We had to stop off at his office briefly so

a colleague could come out to the car and try to sell us some tourist

services and/or ticket booking help.

The throngs and crazy traffic choking

the area around the entrance to

the train station were as we might have expected, given our experience

traveling in other parts of Asia and the world. The touts constantly

approaching are especially notable in India. You finally have

to

pretend they do not exist and continue walking and talking to your

companion accordingly.

The booking office for internationals was an absolute breeze compared

to Beijing. The process was characteristically bureaucratic, but the

final results were superior by far. There were all varieties of foreign

travelers up there, but stress levels were pretty low given that

everyone was being served with a kind of tortoise-speed, but otherwise

pleasant equanimity. The fifty-something, turbaned ticket agent took

good care of us. Food is here. More later.

VI - Room 201

About five minutes free, so I

will write. Happy New Year 2006! It is official. Jenny and I rang in

the New Year sacked out in New Delhi. Given our schedule and circadian

rhythms, this was essential.

I forgot something from yesterday on the way to the train

station. It was a sunny morning and we were riding along a road with a

brick wall set back about forty or fifty feet from the road. We came

around a curve and there were a half dozen cows standing there beside

the road. Around another curve and there was a group of monkeys—little

Rhesus-looking guys that are ubiquitous across non-mountainous India.

The cows and monkeys I knew about. It is the dogs wandering and

sleeping in the streets that I did not anticipate. They are all

medium-small and the same color as the monkeys and the dirt.

VII - Bhopal

Shatabdi Express departing for Agra

We did not have to buy

Indrail passes, and were able to book the entire itinerary in advance.

We walked out of the office yesterday triumphant, tickets in hand. We

only had to make one change in our planned itinerary, adding a day to

our stay in Agra and using up an extra day in Bodhgaya. Not only were

the individual tickets cheaper than the pass, but the availability on

some was in sleeper class rather than the higher A/C class we had

expected. We are very experienced traveling in that kind of lower

class; and who needs A/C this time of year? It will be turned off,

anyway. So that was a pretty big cash bonus for us. [We later learned

there are benefits to a sealed car and the provision of bedclothes in

the cold weather.]

I snagged a couple of liters of water inside the station—first water we

had drunk since getting off the plane. I was feeling pretty dehydrated.

(We are pulling out in the dark, now.) At the prepaid auto-rickshaw

stand, Jenny could not hear

the attendant through the hole in the glass for the tout standing

beside her talking in her ear. She finally turned to him and said,

“Be quiet!”

We hopped into an auto-rickshaw and headed to Connaught Place. We had

picked the best-recommended midrange hotel on the list, and were there

in just a

few minutes. Its modern style and

lesser funkiness made it very appealing. We ate breakfast. It was

delicious—spicy

potato-stuffed buttery flatbreads (aloo

paratha) with hot and salty

pickle relish (achar), and

plain yogurt (dahi) to cool it

off. I am

loving hot chai every time

you turn around—the national beverage. We

were refreshed and greatly encouraged by those basics of food, water

and comfort.

The streets in the daytime were also quite a contrast, with all the

steel curtains raised, all he street vendors, all the traffic, all the

people going about their days. Now it was really looking like the high

adventure we anticipated.

We set out on foot for the Palika Bazaar so Jenny could buy some proper

clothes and gain a little respect. My man clothes already work in

India. On the way, walking around the colonnaded storefronts of

Connaught Place, Jenny stopped to replace her broken sunglasses at a

street vendor. The standard haggle in India seems to be half the quote

and

working your way to two-thirds.

While she did that, I took a picture of a kind of snack vendor we are

seeing around. The snack (masala bhel)

is both visually and culinarily

interesting. Big sheet on the ground. Vendor seated behind with helpers

hanging about. A prodigious

heap of what I can only describe as yellow,

curry-flavored rice krispies (murmura)

on one side. (The train chai

has

arrived.) A pile of minced red onion in the middle. A smaller pile of

minced cilantro, and even smaller piles of minced tomato, chili pepper,

and some crisp chickpea-flour vermicelli (sev kurmura). The heap of

curry krispies has a ring of small tomatoes and lemons, and

green-bean-looking chili peppers decorating its perimeter. On the other

side are a dozen or so rolled-down paper bags of variously flavored

peanuts, perhaps soy nuts, and lentil krispies, and a big pile of corn

flakes. I am not making this up.

A customer comes to buy some.

The vendor grabs two big handfuls of the murmura krispies, tossing them

into a pot, followed by a baseball-sized, all-you-can-grab handful of

the onions. Big pinches of cilantro, tomatoes and peppers, some corn

flakes, a couple of selections from the other nuts and krispies,

squeeze in half a tiny lemon and add a pinch of salt.

(It is getting light and the trees passing near the train are just

visible against a shroud of blue-gray pea soup fog. Oh, wait—the window

is tinted purple. Breakfast has also arrived. A couple slices of

unbleached white bread, a pat of butter, and some garish,

syrupy-tasting jam on one side of the tray, and potato, peanut and

coriander stuffed samosas with a packet of ketchup on the other.)

Anyway, the vendor tosses

all this in a pot and stirs it round and round, spoons it into an

envelope made of newspaper, garnishes it with the crisp chickpea-flour

vermicelli, and serves it with a little wooden ice cream spoon stuck

in it.

|

The snack (masala bhel) is both visually and culinarily interesting. |

The Palika Bazaar is a couple of large, concentric, oval tracks of numbered merchant stalls, all indoor and underground. There are some crafts and electronics, jewelry, etc., but the main thing is clothes, pretty much aimed at locals.

I followed Jenny around as she cased all the shops (200-some in all), and then we went in one. They displayed the equivalent of party dresses, but Jenny explained that she wanted non-fancy, everyday clothes. The style of shop keeping was positively old-world. The merchant pulled considerations off the shelf one after another, immediately tossing aside any that were met with “nah” sounds. Jenny explained her color preferences and things began to narrow down. This was the best of that kind of sales-ship—no pressure. He liked what she liked. She picked a couple of beautifully colored and subtly decorated sets of salwar kamiz and dupatta. She looks beautiful in them, and she declares that despite their exotic beauty to us, they are extremely comfortable and practical and she feels good in them.

They come sleeveless and we followed an assistant to the loft of another stall so a tailor could measure Jenny for altering the waist on one, and adding the basted-on optional short sleeves to both. She bought a third set at another shop, and picked out some earrings, bangles, and a hippie bag.

Back at the hotel she tried on the clothes while I wrote about the outcome of our hotel woes, and then she put on one to wear, hiding the creases where it had been folded with the way she wore the dupatta. She will wear these for the rest of the trip.

We set out on foot again, this time to the Janpath market, which seems largely dedicated to Tibetan crafts. It was such a pleasant late-afternoon walk. We bought what are basically curry potato stuffed turnovers with chili sauce, and munched while we walked. I was noticing the way Jenny was regarded in her Indian clothes.

At the market I bought a small, heavy, lidded brass bowl for Dave’s (my late brother’s) ashes. A tout outside said “Hello! Chess set!” Jenny said, “Did he just say ‘Hello cheese pants?’” Around the corner on a perpendicular side of the market I photographed sellers of ornate, Tibetan throw pillow shams, table runners, bedspreads, etc.—all women. (It is getting light and we are nearing Agra.) More later.

VIII - Table in the garden, Hotel Sheela, Agra, Uttar Pradesh

After the Janpath market we strolled back toward the hotel. As we were making our way back around the inner circle of Connaught Place, I saw another masala bhel vendor and decided to sample some. I pointed, nodded and smiled. He smiled back with a hopeful look and made a stirring motion. I nodded again. In went the krispies, the astonishing wad of onion, and all the rest. My newspaper envelope was made of four-color ads. Its contents were delicious. The tomatoes (unpeeled) and fresh cilantro both broke a cardinal rule of street-vendor grazing, but they were in small amounts and I was just sampling. Jenny reminded me about this, and then sampled a bite herself.

We strolled and I munched. Vendors were hawking these large, foil-covered, conical cardboard horns that made a loud, low sound, sort of like a party horn on steroids. Of course! It was New Years Eve. It occurred to me that it was not going to be a quiet night on the street below. Jenny reminded me again not to eat too much of the bhel.

Once inside the hotel we bought thirty minutes of internet access and e-mailed home that we were fine, and with an explanation of our itinerary change. After that we went to the room, changed into pajamas, ordered the Indian room service mentioned above, ate it, got organized, and fell into bed. It was about 8:30. Happy New Year.

Well, I learned to distinguish between the party horns and car horns as I dropped off to sleep. The party horns had a slightly quieter, somewhat remote sound, and reminded me of continuously honking geese, but stationary geese, spread curiously throughout the city, both near and far. This was punctuated by the car horns, which were both closer and louder in their electrified power. With the roar of motor traffic in the background, it made for a fairly unified and interesting overall texture. Cage would have been pleased. So, too, any Dadaist worth his salt.

We managed to sleep fairly well, though. Better than the night before, anyway. The jetlag was actually a plus, given that we would have to rise at some ungodly hours, for the train to Agra, for the Taj Mahal at sunrise, and for boating on the Ganges at dawn.

|

Sellers of ornate, Tibetan throw pillow shams, table runners, bedspreads, etc.—all women. |

|

We felt fairly alert at 4:30 when the

travel alarm beeped. We checked out and the elder, turbaned,

mustachioed Sikh taxi driver got us to the station in short order.

Nothing but foreigners in the “executive

seat” cars attached to the

Bhopal Shatabdi Express, expressly for the tourists who board for its

two-hour segment from Delhi to Agra, where the Taj Mahal is located.

Aussies, followed closely by Koreans, best represented this population.

Everyone had a Lonely Planet

guide in mother-tongue translation. Lots

of backpackers as dumb as I was when I

was eighteen, but a wide range

of ages, all the same.

The chai

and breakfast described above came and

went. For some reason the two-hour trip took three. The train was very

evocative of China for me. Only the Indian faces and Hindi words on the

ad boards were indicative of India.

It was another bright, sunny morning. I

got us a prepaid taxi at the outdoor booth. To cut acid rain

damage to the Taj Mahal, no new industrial development has been allowed

in Agra since 1994 and all three or four-wheeled IC motor traffic is

banned in the vicinity of the Taj Mahal. The driver dropped us at the

perimeter and we transferred to a pedal-rickshaw. There were also

electric busses operating in the area.

The hotel is outstanding, even though it is a bottom-end place selected for location. A large, red sandstone paved plaza enclosed deep within a quiet, pleasant garden far from the noisy traffic. We sat with our backs to the morning sun sipping tea and waiting for checkout time so we could check in. Well-tended ficus, palms, cypress, bougainvillea. Later we watched parrots out in the garden.

Because the hotel falls well within the

low-budget option for those hailing

from industrialized nations, the funkiness factor is very high in

the rooms; but this is more than compensated by the pleasantness

outside where everyone hangs out, and the quiet day and night. More

expensive options include the din of motors and motorcycle horns day

and night. The elderly Sikh gardener gave Jenny a tiny,

string-wound bouquet with a little piece of juniper and a single

marigold

blossom.

We ate a second breakfast alfresco

after

check-in, and

then strolled the streets. I have seen and ridden both donkey carts and

camels in various places, but this marks my first time seeing them

combined in the

form of camel carts. Cows milling about as expected, goats, etc. The

gate of the hotel garden is fifty meters from the east gate of the Taj

Mahal.

IX - Hotel garden

(continued)

We stopped at a large state licensed emporium for marble inlay items

that apply the same craft as the inlays decorating the Taj Mahal.

There was a group of craftspeople working there, shaping inlays on

grindstones and hand carving their shapes in marble. They were making

tabletops.

There were several large showrooms, one of which held the most

exquisite and precious examples of the work. It was like a museum.

There were also several examples of innovative inlay work, based, we

were told, on

more Euro-American aesthetic concepts, but applying essentially the

same ancient Persian techniques of craft. I was impressed with the

interest in innovation and in broadening the scope of work to appeal to

a variety of aesthetic sensibilities.

The taxi driver from the train station said

four o’clock was a good time to go to the Taj Mahal for being

there at sunset, so we set out about then.

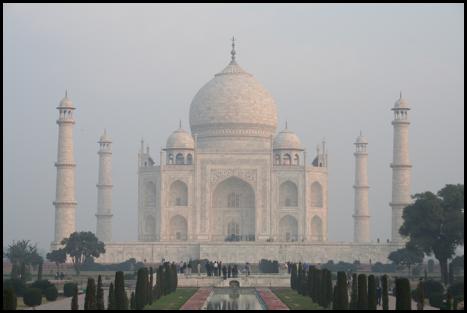

After one enters from a side gate there is a plaza with a colonnade on

the south side and the side gates east and west, all red sandstone. A

wall runs along the north side of the plaza, and in the center of that

is the great gate of the Taj Mahal. Walking along from the side gate

where one enters, the dome and minarets of the Taj Mahal become visible

over the red sandstone north wall. We both found ourselves unexpectedly

moved when that much of it came into view. It really is magnificent.

After coming through the interior of the massive red sandstone gate

(decorated with white marble), we stood on a porch at the top of steps

going down to the garden and pools, looking across a seemingly great

space at the massive monument sitting on its wide plinth. At that

distance and perspective I had the sense it was enormous. Coming

closer, it seemed to become more intimate. Have I written that

it is magnificent? I was moved again to see it like that. It really is

magnificent.

We walked down along the reflecting pool. There is a marble platform

halfway along that affords another raised view, and on the north side

one may squat down and get a view of the tomb with its reflection in

the pool.

|

A large, red sandstone paved plaza in a quiet, pleasant garden far from the noisy traffic. |

When we reached the plinth, we decided to stroll around it and save going up on it and inside for the next day. The plinth itself is a couple of stories high. Along the backside of the court below it is a very low balustrade where there is a drop-off three or four stories high along the foundation, down to the riverbank below. Dangerous and scary.

Though there were respectable crowds there, few people walked to the plazas on either side and around behind the plinth. It was a singular stroll, looking up at the Taj Mahal from there as we walked. It was also impossible to compose photos that could convey the experience. The human mind can compose any number of well-framed details and then compile them into the whole field of vision at once, while still maintaining singular comprehension of each detail. No photograph can do that. All we could do was try and capture a few details. Jenny and I have a saying about consciously creating a memory of something both compelling and passing: “Take a picture.”

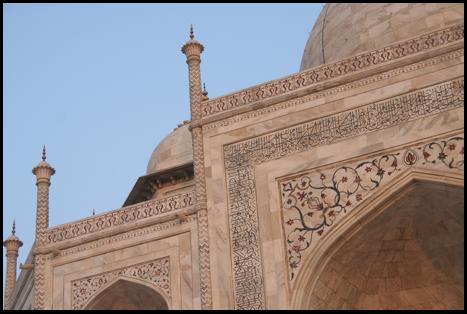

There were people in a park across the river getting the identical rear view from there. It is the same from all four directions, minarets included. The only difference is in the Arabic scripts inlaid in black marble framing the large central entrances. Surely they are Quranic, though I do not know what they say. There is something to research.

After strolling around the backside, we walked back along the wide, red sandstone path on the east side of the central garden and pools. There are other well-tended gardens outside there to the east and west, with a variety of trees, all catalogued and labeled. Dark was falling and it was so pleasant.

|

All we could do was try and capture a few details. |

|

The electricity in ordinary Agra (like, not the Sheraton) is undependable, as with many such parts of the world. The electricity at the hotel goes off every so often. If that lasts for more than a few minutes, they start a generator, but it seems to just stay off much of the afternoon. We sat at a table under a steel awning outside for dinner. It was dark, and the lights kept going off, but we had a candle. I was feeling a little travel bug coming on, so I tried to eat modestly.

As we were going to try getting up

early to see the Taj Mahal at dawn, we switched off the extremely dim

fluorescent light in the room (it is like moonlight, to put it in a

positive way), and crawled into bed. We asked for extra woolen

blankets, so we stayed warm enough in that dark, dank, thinly

veneered little concrete box of a room. I am sure during the dry season

having a room ten or fifteen degrees cooler than outside is a real

plus. This is the only budget hotel on our trip. All the rest are

midrange.

X - Hotel

garden

(continued)

I did not feel well when we turned in, but slept soundly. One of the

two times I remember waking, I felt ill, so I knew I was fighting a

bug. This morning I show signs of an effectively rallying immune

response. I have had this exact thing abroad in Asia several times

before, and this has been the shortest cycle of it.

It was still dark when we rose. I

checked at the desk for breakfast at the time we had been told, but

except for the lone, watching attendant, everything was dark and there

were some workers sleeping on the floor of the reception room.

The attendant named a time an hour later. Jenny always needs breakfast,

and going back to the Taj Mahal without it would have made her ill. On

the other hand, I wanted to be there at dawn.

After hanging out in the room for a

while (in the “moonlight”), we decided I would go to the Taj Mahal

then, while Jenny ate breakfast, then she would come in and meet me

there later. I set off right away.

Going in, I was as moved as the day

before. It was getting lighter, but it was a hazy morning, so the light

was just a gray color turning slightly more golden as the minutes

passed. I am convinced that Lonely

Planet photographer used an orange

and purple gradient filter for the picture on that plate in the book.

I could sit down on the top step of the gate porch and

still get a perfectly unobstructed photo over the heads of all the

people who were moving down to the middle tier of the porch to take

pictures of the Taj Mahal, or have their pictures taken in front of it.

I sat there for thirty or forty minutes watching it change. Every time

I looked up from fiddling with the camera the

Taj Mahal had changed appreciably with the approaching sunrise. Sitting

there watching it change like that is an experience I hope not to

forget.

Finally, a woman in bright blue salwar,

lime green kamiz and matching

two-color chiffon dupatta

came and stood beside where I sat. Without

looking up I knew it was Jenny. “Hi, there,” we said.

Halfway down the garden on the north

side of the raised marble platform at midway, a friendly Dutch guy took

our picture with our camera for us. He asked some Japanese tourists in

Japanese to please move. He was composing the shot well, and we knew

that he knew what he was doing. We saw him again later up on the plinth

around on the backside taking photos of details. Later, on the way

back, we asked this European woman to take our picture again. She

actually cut off the dome in the picture. Jenny said, “Everyone has

different gifts.”

When we saw the Dutch guy the second

time we struck up a conversation. His Dad had been in a Japanese POW

camp, and taught his son what Japanese he had learned. Later on, here

came the guy walking into the garden of the hotel. After that, here

came the woman who had taken the bad picture and the woman with her.

Best place in town. (There is a bright blue kingfisher with an orange

breast, black head, and yellow beak sitting in the tree.)

We walked on to the Taj Mahal. On the

plaza below the plinth we were given blue surgical booties to put on

over our shoes, to protect the solid white marble up on the plinth and

inside. The sun had come up and it was beautiful up there.

I took macro shots of the floral design

pietra

dura inlays on the porch: carnelian (red-orange), malachite

(green),

lapis lazuli (blue), abalone (pearly), jasper (dull yellow), and black

marble. Precious stones of the ancient world, and of St. John’s

apocalypse.

Inside, the inlays on the styles and

rails of the octagonal marble filigree screen were different from those

on the outside, and I liked one of the patterns (little bunches of

vase-shaped carnelian blossoms with tiny inlaid stamens), but photos

were prohibited and I could not manage one without getting caught at

it—made me think of Jenny at the terra cotta warriors in Xi’an; but her

treachery was an unqualified success. No matter—it was dark in there,

anyway. Every

time I looked up, the Taj Mahal had changed appreciably with the

approaching sunrise.

The single marble filigree lamp (fitted with an electric

bulb) hung from a very long chain attached to the ceiling in the base

of the dome. It swayed slightly as such long pendulums do. Something to

do with the Earth and Paschal’s observations.

Her white, inlaid sarcophagus is in the

center on an inlaid platform. His—larger—is to one side on a slightly

higher platform. The actual bones are supposed to be in the basement. A

railing kept people away from the screen, but one could walk all the

way around it and see the sarcophagi through the door of the

screen. The reverberation was spectrally full and long. Someone was

singing something loudly as we walked back out.

We walked around the building the

opposite way we had walked round the plinth the day before and we saw

the Dutch guy the second time. We came down

and back through the front garden. I took photos and the woman

took

the bad picture of us. We walked backwards a little, looking at the

whole

thing. As we walked out, I remarked how lucky we were to have

experienced it.

|

I took macro shots of the pietra dura inlays on the porch. |

|

After a riot of Indian food, I am

appreciating the merits of plain toast and plain tea in my delicate

condition. That is what I had for breakfast back in the hotel garden.

After a while, Jenny set off on foot to find a post office for stamps

to send post cards, and other things we might need. I stayed in the

sunshine of the garden and wrote. After a while she came back with two

gray, army-like wool blankets for the rough-class overnight train trip.

This on the way to find the post office.

She had walked alongside a bull in the

narrow street, which had sort of lightly butted at her as she had

passed. A man called to her from across another narrow street. “Where

did you get your earrings?” Jenny ignored him, so he said, “What, you

don’t talk to Indians?” Up went the dupatta.

He said, “I see you are

covering your hair, but I am still going to follow you.” That was the

end of it.

She stopped at a place with a woman

working at it and asked for bindhi (tiny,

adhesive, jewel-like forehead decorations). The woman asked, “How many

do you need?” “Oh, just one.” “One bindhi?”

she asked flatly. “Oh, maybe five or six.” I suggested

later that they must come packaged multiply, like matches in a box, and

that if you replace “bindhi”

with “matches,” you can see the woman’s perspective. “How many matches

do you need?” “Oh, just one.” “One match?” “Oh, maybe five or six.” We

have laughed about that several times today. The woman told Jenny to

come back later.

I had coffee with my toast at lunch.

After lunch we walked out again. We went back to the place Jenny had

bought the blankets and she got a cardigan. Women wear them over their kamiz. It is cool at night, and we

will be on the drafty train. I bought a fleece vest. We walked the

narrow, open sewer lined streets. The shops were more like stalls, as

seems typical.

The woman still did not have the bindhi, but she said to come back.

At that point I was feeling kind of weak, so I headed back to the hotel

and left Jenny to her “third-world, dusty-donkey adventure trip,” a

phrase I had uttered at lunch and we had laughed about.

Back at the hotel, I lay down and

thought about details of the committal of part of Dave’s ashes at

Varanasi and Bodhgaya. As I thought about reading the scriptures and

prayers we had prepared, I began to cry. I felt better after a while,

both emotionally and physically, so I went out to the garden to sit and

write.

Jenny came back

with a bindhi stuck on her

forehead, and mendhi on her

left hand and wrist (intricate designs painted on with henna). I

thought if left to her own devices something like this might happen. It

is beautiful.

It is dusk now, and we have been

sitting here at a table in the garden, Jenny reading and I writing. I

think I will skip dinner. The gentle, friendly server/food manager

Anil has brought us a candle.

XI - Hotel garden

I slept well and felt much better this

morning. It was probably that masala

bhel, after all. I have been meaning to write that we hear calls

to prayer coming over a loudspeaker from the mosque inside the Taj

Mahal. The day we arrived, there was also what sounded like Hindu

chanting coming from a loudspeaker somewhere.

We had a leisurely breakfast. I am

expanding on the theme of plain toast. This morning I had the Indian

version of French toast with some honey. Also, a fruit lassi. That is a glass of small

mixed fruit chunks (papaya, apple, sultanas) with sweetened drinkable

yogurt poured over. Yum!

A mixed-nationality tour group came in

last night, waking us briefly. They were all sitting in the garden this

morning listening to a lecture about what they were about to see,

having been adorned every one with a garland of marigolds. Their guide

was a slick-looking, gregarious Indian fellow. Group tours. No, thanks,

all the same.

We checked out. The bill for two

nights’ stay, seven or eight meals, and laundry, was astonishing in its

modesty—about forty-seven dollars, total.

After paying up, we packed

up. After having acquired a blanket and a sweater each, it was time for

the hand-roll vacuum bags. Our clothes had come back from the

laundry-wallahs, pressed boxer shorts and all, and we compressed them

to make room for the other stuff.

We stowed our bags for the day and

went to buy some gem-inlaid marble items. From a design standpoint, I

can understand Vicki’s (my sister’s) interest in the Taj

Mahal (she is a commercial interior designer). Apparently, the

aesthetic and craft are Persian in origin. We are going to need an

extra bag sooner or later if we keep buying loot.

We added the new purchases to our stowed luggage and caught an

auto-rickshaw to the Agra fort. It is a massive red sandstone affair on

the opposite side and up the river from the Taj Mahal. The grandfather

of Shah Jahan (builder of the Taj Mahal) built the fort.

Shah Jahan began to turn it into a

palace during his reign, planting gardens, installing palatial

buildings made of his personally preferred white marble, and plastering

over existing red sandstone structures to make them white. He also

built a high-perched overlook from which he could gaze upon the

monumental tomb of his dear departed down the river. The haze was way

too thick to see it today. The whole thing became his gilded prison for

the last thirteen years of his life, after his son deposed him. Junior

was kind enough to inter Dad in the Taj Mahal, next to Mom.

Various invaders have occupied and/or

plundered the fort over the years, the last being the British, who used

it as a garrison. The hall for receiving dignitaries had contained the

solid gold peacock throne. The Persians carted it off at some point,

and it was last seen at the coronation of the Shah of Iran.

Jenny looked stunning in her pale blue salwar kamiz against the white

marble. A group of Chinese tourists passed by, and a woman remarked of

Jenny (in Chinese), “Very pretty.” Here is this blonde, blue-eyed woman

in a strikingly blue Indian garment with her head covered in a dupatta and a sparkly thing on her

forehead. Jenny then thanked the woman in Chinese. That slowed them all

up a little bit, and then Jenny said in her perfect Mandarin, “So, you

all are Chinese?” Talk about messing with someone’s head. They were

perfectly gobsmacked. The woman sputtered, “Are you Chinese?” Then a

man was saying, “So, this is a sa-li

(sari)?” Jenny said, “It is salwar

kamiz.” They all looked puzzled, then I said in my perfect Mandarin, “This kind has

pants and a shirt.” That got them again. The man said, “You, too?” They

were from Shanghai, and clearly having fun.

We had the auto-rickshaw driver drop us

off short of the hotel, near some shops, and set off to find a bag for

the extra stuff we are buying. Jenny bought a garland of roses to give

to the owner of the hotel. He seemed genuinely pleased.

I had a toasted chicken sandwich for

lunch. The chicken was chopped and fried with onions and curry. The

French fries (“potato chips”) were tasty, too. I have been sitting here

ever since, writing and chatting with Jenny. She went out once to get

some tikka powder (for

forehead dots) and these wooden tea boxes we had seen, but scored on

neither. The sun is going down on this cool, hazy day, and it is

getting cooler. We have about two and half hours to veg. out here, but

part of that will be for dinner.

XII - Marudhar

Express to Varanasi

We vegged out. I ate a light dinner of

some naan (roasted flatbread)

and the equivalent of egg-drop tomato soup. We gave Anil a big tip—hope

that was okay. It got cool enough outside that we moved to one of the

tables inside the reception area. There were goofy (to us) Indian music

videos and commercials, the latter of which were as goofy as any,

anywhere.

The train tickets indicated which

station, but the same train stops at all four stations in Agra. We had

lots of advice from hotel staff about which station to go to, but we

decided to stick with the instructions. One staffer was really nervous

and kept asking if we should not leave.

There was but one auto-rickshaw there

in the dark street. The driver was a little wilder than some with his

driving, so the commute bordered on harrowing. The departure

station was tiny for a city the size of Agra, and few people were

there. Included among them was an Australian hippie backpacker couple,

and an old man with withered and twisted, but still useable legs,

walking with a stick.

|

He built a high-perched overlook from which he could gaze upon the monumental tomb of his dear departed down the river. |

The train arrived more or less on time, and is now approaching its final destination this morning, it is only about an hour and a half late. It is like a Chinese hard sleeper in every way, except that the people look and behave differently. I took the upper of the longwise, aisle-side berths we had been assigned. The turquoise-blue vinyl of my berth was encrusted with silty dust. I managed to wipe it fairly clean with some damp toilet paper.

I could not figure out how to turn off the glaring fluorescent light, so I just covered my head along with the rest of myself. That is how all the people around us were sleeping. After about an hour of sleep the conductor came around. After he checked the tickets, I heard the snap of a switch and the light went out. The berths are a little hard on hips and shoulders, but I managed to turn often enough to make it through the night without waking for very long.

The berth was too short to stretch out on my back, so my bent knees had to lean against the wall. The wall would shudder and rumble loudly with the sudden wind and noise of a passing train, and give me a rude awakening. The windows tended not stay all the way down, so the car was breezy and cold, but we stayed warm enough in layered clothes, covered over with blankets, under which the warmth of our breath stayed. At some point, the person on the lowest of the longer, crosswise berths adjacent to us got off, and I moved there so I could stretch out. Jenny noted that the man down there had a blanket just like ours, and that the top of his head looked like mine, before she realized it was I.

We are organized and ready to

disembark. We are looking forward to a

hot shower and some clean clothes, and then to striking out along the

ghats. I bought two tiny, steaming cups of chai from the roving vendor,

and we got into the beef jerky again. Jenny reads that the rooms at our

midrange hotel have mini-bars.

XIII - Lobby

restaurant, Hotel Pradeep, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

We snagged an auto-rickshaw to the

hotel. The uniformed guard saluted us. They showed us a couple of rooms

from which to choose—no windows, but nice enough. The bathroom is

beautiful, though there are large frames of screen-wire ventilating the

plumbing shaft between our shower and the one in the room next to us.

This provides a picture-window view from one shower to another.

Apparently one of our neighbors was aware of this, too. He stepped into

the other bathroom once saying, “Hello? Hello?” to make sure it would

be decent to use at that moment. I thought the mini-bars were too good

to be true; I was right. It was still much more comfortable than in

Agra.

We ate a hearty breakfast in the lobby

restaurant

and took hot showers (the neighbors were gone). I felt just

squeaky afterwards. We unpacked some laundered clothes and put them on.

We took an auto-rickshaw toward Dasaswamedh Ghat. No motor traffic is

allowed in the old city, so he had to drop us at some distance. We

strolled slowly and looked the all the interesting color. Jenny bought

a couple packets of tikka

powder (dry forehead-dot paint) from a vendor

whose intensely colored piles of the stuff were laid out on a cart. She

chose colors to match her outfits, which is typical, save the reds and

oranges, which are more traditional and indicate religious devotion.

Back in Agra we had chatted with the

people in the

big, mixed tour group. One of them was a funny, young

Australian woman. As she was

walking out toward the gate of the hotel garden waving a twenty-rupee

note, she said of the group, “I’ve turned them on to samosas, so now I

have to make a samosa run.” Jenny had chatted with a young Irish man in

the group (whose accent was almost American) about their travels, and

found out they were also headed to Varanasi. That evening they were

piling their packs up in the garden plaza for a trip to the train

station around the time we were waiting to depart, but we found out

they were going on a different train, from a different station in Agra.

XIV - Rooftop

garden, Hotel

Pradeep (continued)

The next day in Varanasi, while were getting Jenny’s tikka powder, I felt a

tap on my shoulder. It was the young Irish guy.

After Jenny and I walked toward Dasaswamedh Ghat for a while, we

decided to get a cycle-rickshaw, not only for the conveyance itself,

but also because we did not know exactly how to get there, and the

cycle-rickshaw driver would. Even two American butts in as good shape

as ours are a tight squeeze in one of those things. I had seen a

fifty-something Indian couple in one. The man had shifted to a slight

tilt so the woman could sit flat, so I adopted the same technique.

We alit at the end of a lane at the top

of

Dasaswamedh Ghat, and the last vendor in the lane was a woman selling

beauty notions. Jenny bought a couple of cards of bindhi from her, and

she adorned Jenny’s forehead and hairline with spots of deep red tikka

powder. A spot at the hairline (a line in the part, if the hair is

parted) indicates a married woman.

|

We strolled slowly and looked at all the interesting color. |

|

We walked down the long, long steps of

Dasaswamedh Ghat (it is perhaps thirty or forty yards

wide). The first thing I noticed to the left was the

huge, orange-painted sikhara

(Hindu spire indicating a temple) at the adjoining ghat to the north.

The ghat we were on opened out wider to the south, below the buildings

facing the river. We strolled in that direction and saw a priest

sitting beneath one of the round, reed-woven umbrellas where they sit.

There were some musicians there, an older man playing a harmonium,

and a younger woman playing tabla

(drums) and singing for all she was worth. We sat down with the others

who were hanging out there and listening.

As we sat, we noticed men going to the

priest (a fairly young one) to be blessed and have marks painted on

their foreheads, after which they made a small donation. Jenny

encouraged me to participate (she was right—when would such a chance

come again?), but I was resistant. As we sat there, I decided on my own

to risk making a fool of myself in exchange for an experience I would

not forget.

I ventured to the platform and under

the umbrella. The priest was peaceful and welcoming with his smile, and

the singing, drumming woman was clearly pleased. I had seen a couple of

different types of applications, and when the priest gestured, asking

if I wanted tilak (a kind of

three-stripe pattern painted clear across the foreheads of devout Hindu

men), I indicated “no” and made a gesture for “little.” He understood,

and I squatted down. He dipped his finger in some deep orange liquid tikka, followed by some intense

yellow. He touched my forehead with it and held it there while he

chanted quietly. It certainly had a blessed feeling to it. He offered a

mirror. The result on my forehead was a deep orange, finger-sized spot

rimmed in yellow.

|

She adorned Jenny’s forehead and hairline with spots of deep red tikka powder. |

I bid him namasté and gave him a few

rupees baksheesh, and also

the musicians. The woman laughed delightedly, made a beckoning motion

with her fingers and teased, “More!” so I obliged. As we walked back

the other way I remarked to Jenny, either it was a blessing or he sent

me back as a dog, and we chuckled.

There are over eighty ghats

along the river. Dasaswamedh is about the most central, and those

around it, especially to the south, are brightly painted and stand out,

as seen from the river. The plan, after consulting descriptions in the

guidebook, was to start there and stroll north until we felt we had

seen enough. Little did we know how that would culminate.

Boys have been flying

small, paper kites all over Varanasi since we arrived. ‘Tis the season,

and apparently that season ends in nine more days with some local

festival. As I sit here in the rooftop garden of the hotel, I can see

three or four every direction I turn my head. They are being flown from

the rooftops around and below me.

So, there were also boys

running along the ghats, flying them where we strolled. They could get

the little things airborne rapidly, keep them there, and manipulate

them. It seemed like they were impishly conducting them in our

direction, by their behavior and the looks they were giving us.

|

The

priest was peaceful and welcoming with his smile, and the singing,

drumming woman was clearly pleased. |

|

I bought a sack of glass beads from a woman selling them, and Jenny took a picture of her sitting with her layout. In areas where there was more foot traffic and things being sold, the ghats were being hosed off and swept down with water pumped up from the river, but in other areas the cow shit and urine and general slime were rather off-putting. Jenny remarked that to slip and fall in it was not a memory she would like to make.

Finally, we came to Manikarnika Ghat, not too far upriver from where we had started. We knew about it, but were not concentrating on the nature of the ghats we saw, or which ones we were at. We just rounded a structure and it was upon us.

It is the main cremation, or “burning” ghat. It is disrespectful to take photographs, and everyone we saw, both on the bank, and later in boats on the river, kept their cameras down. Wood was stacked everywhere, according to type, ten and twenty feet high, and the air was thick with smoke. A sense of sacredness, awe, reflection, and consternation came over me. Our own taboos were challenged by something I otherwise knew to be both deeply sacred and superlatively ordinary.

We sat down on the ghat for a moment, as others had done upon arriving. I was aware of the nature of the activity, but without an orienting perspective on it, just yet. The work was being carried out on large, stone or concrete platforms built across the lower portion of the ghat, and I was conscious that we would have to climb higher to circle past.

|

I bought a sack of glass beads from a woman, and Jenny took a picture of her with her layout. |

XV

- Platform 6, Varanasi Junction (continued)

After sitting for a moment, we rose and started up and around. I asked

someone if I could take a picture of a stack of wood that was up the

ghat in the opposite direction of the activities below. He said it was

okay, but after I took it, an old man indicated there should be no

more. Moving along behind some outbuildings above the ghat, among the

stacks of wood, we came to the entrance of a cupola-topped, circular

balcony overlooking the ghat. There were people inside the pavilion to

which it was attached, but we had the little balcony to ourselves

(except for one adolescent boy who tried for a while to insinuate

himself as our guide), and we were concealed from the foot traffic

behind.

(The train will be a couple of hours late. I chatted with a half-dozen

grownup U.S.Americans traveling with Tenzing from Mongolia [a Tibetan

monk], who had not heard the announcement. They are going to the same

place we are.)

Looking down on the stacks of wood,

they were distinguishable as having been sorted into different types by

their contrasting shapes, sizes, colors and textures. They were not cut

cord, rick, fireplace or stove length as is familiar to us, but in five

or six-foot lengths, which were more naturally curved and twisted, as

such.

|

In

areas with more foot traffic and things being sold, the ghats were

swept down with water. |

|

Lonely

Planet says this: “Huge piles of firewood are stacked along the

top of the ghat, each log carefully weighed on giant scales so that the

price of cremation can be calculated. Each type of wood has its own

price, and sandalwood is the most expensive. There is an art to using

just enough wood to completely incinerate a corpse.”

On the surface of the platform below us to the right were three active pyres, the fires and contents of which were being actively tended using long, thick, green bamboo poles. Observing the details closely would not be for the faint-hearted. Jenny, who has seen more than I, gravely and gently observed some.

Bodies were carried on stretchers,

swathed in intensely colored, brightly glittering cloth and garlands. I

understand colors indicate sex and relative age of the deceased. Bodies

were carried right down to the water and doused in the Ganges, then

placed on the platforms where pyres were assembled over each. (Bodies

are handled by outcasts known as doms.)

Groups of people stood by, presumably family members.

I read that only male members of the

family stand vigil as the body is consumed. Females fulfill other

ritual roles elsewhere during that time. It is also considered

imperative that the family members present remain there until the

process is completed in its entirety. Ashes are gathered into red

earthen jars rounded into a spherical fishbowl shape. I saw these

stacked up by one of the outbuildings we had passed. Ashes are then

scattered out in the Ganges.

|

Wood was stacked everywhere, according to type, ten and twenty feet high. |

(The train should be here in about

fifteen. Bag of potato chips and a package of biscuits [cookies] on the

platform for dinner. Jenny arranged for someone from the hotel in

Bodhgaya to meet us at the station when she called from Agra to make a

reservation.)

XVI - Same platform

The arrival time for the train has just been pushed back another hour.

Jenny headed for the WC. A young, black bull just sauntered up the

platform and sniffed at our bags. I casually shooed it away. Back to

yesterday.

Being at the burning ghats was intense, and mentally and emotionally exhausting. We decided we had enough of the ghats for one day. We worked our way back down them, over the cow slick, and back toward where we had come in. As we moved away from Manikarnika Ghat, the air was thick with the aroma of sandalwood smoke.

Jenny properly discerned a shortcut, and we made our way up a backstreet to the road by which we had come. We caught a cycle-rickshaw to get back to where the auto-rickshaws waited. The cyclist wanted to take us all the way back to the hotel, but I felt pretty wasted and thought it might take forever.

Back at the hotel we slaked our thirst with a liter of water, retired to the hotel’s extremely pleasant rooftop garden, and dined on a very encouraging dinner of chicken tikka and rice, fresh lemon soda, and chai.

We regrouped and headed out to Assi Ghat (the southernmost), and to the hotel’s sister establishment for a tabla, sitar and flute concert. The other hotel was hot inside, hopping and noisy with Euro-American tourists. It turned out for some reason that the concerts were off for three nights, including that one.

The electricity in Varanasi was rather more dependable than in Agra. The two or three times it did go out, there was no more than a minute’s lag between either its return or the hotel’s generator kicking in. That was good, considering you could not see your hand in front of your face in the windowless room. On the way to the hotel where the concert was supposed to be, I noticed a portion of the city through which we passed was without power. A few shops/stalls had generators and a few lights, but most had kerosene lamps or candles going. The other hotel shone like a beacon.

We decided to try that hotel’s rooftop restaurant for a snack, but it was partially under construction, lit sparsely and garishly with bare bulbs, and would have been generally unpleasant. Back outside in the dark, the lone auto-rickshaw driver quoted us a fivefold price, so we laughed and walked off toward where there would be others. In another minute he caught up with us, quoting a customary price.

Back at the hotel, we saw through the big window between the lobby and restaurant that the large, mixed tour group from Agra had come there to eat dinner. The funny Australian woman hollered and jumped up and we stepped into the restaurant to their acclamation. The Irish guy said, “There’s the guy that’s been stalking me.” I said to the woman, “The samosas are just down the road, in case you were wondering.”

We came back down there to have dinner, ourselves. The group was going around the table hearing testimonies about what their trip had meant to each one of them. Some kind of saucy, spicy chicken biryani (seasoned rice) and more aloo paratha for me, and it was time to hit the hay.

That afternoon after the ghats, I asked

at the hotel front desk about buying offering candles to float on the

Ganges, and the best time to start a pre-dawn boat trip, explaining our

intentions in addition to a tour of the ghats from the river. A tour

guide with the hotel set it all up for us. It was a real load off my

mind after the stress of the ghats.

We were retiring late and getting up early again, but after the chilly room in Agra and the hard berths on the train, that soft, warm, clean bed looked like heaven. We were not disappointed, and slept well.

During the precious snooze of the travel alarm, the phone rang with the wake-up call the guide had promised, even though we had told him not to bother. When we found him in the lobby wearing a down coat and furry hat, I thought my fleece vest might not be enough. Confirmation came when we stepped outside. Jenny waited while I ran up to get more layers. It was chilly, but we were okay. The guide slipped in next to the driver of the auto-rickshaw.

We put in at Shivala Ghat, quite away south of the ghats we had been at the day before. The boatman rowed northward three or four ghats until we were opposite Harischandra Ghat and a little way out from shore. We stopped there, as arranged.

When we had walked down Shivala Ghat

toward the boat, we were met by a cheerful little boy in an open-faced

ski mask with a basket of the candles we had asked about—about a dozen

of them. We bought the lot from him and he accompanied us out onto the

boat to assist, carrying the basket of votives with him. The guide had

been sweetly affectionate with him, tweaking his cheeks and patting his

head. They

were in your memory, Dave.

Harischandra is one of the oldest of all the ghats in this, one of the

oldest cities in the world; Varanasi dates from two millennia BCE.

Harischandra is also a cremation ghat, and the wood was stacked as at

Manikarnika Ghat. It was also stacked high in boats moored at the ghat.

The votives each consisted of a small

bowl shaped much as a small, paper picnic bowl would be, except molded

of some kind of broad, brownish-green, dry leaves (betel leaves, I

think).

Each bowl served as a little boat. In the center was something

like a tea candle, surrounded by a ring of marigold blossoms.

When we boarded the boat, the

little boy began taking something soft and white from a small plastic

container and forming it around each wick. I have no idea what it was

(yak butter is a possibility), but perhaps it fueled the wicks in the

breeze until the

wax began to melt and wick to the flame. He began lighting them, until

the guide explained that we would be putting them into the river

elsewhere.

When we stopped opposite Harischandra

Ghat, the boy began lighting the candles and handing them to Jenny and

me, and we, in turn, laid them on the water. They floated away behind

us and Jenny took photos. They were in your memory, Dave.

I took the cardstock with a scripture

from the Upanishads and a blessing from

the Book of Common Prayer printed on it out of the yarn bag I bought

from Uighurs in China; and, I also

brought out the lidded brass bowl from the Janpath market in Delhi, now

containing half the portion of Dave’s ashes we had brought along. As we

untied the piece of selvage holding on the lid, the guide commented

admiringly on the bowl.

I set it on the seat board and read the

Upanishad aloud, feeling like I did a brave job of it. I picked up the

bowl, removed the lid, said, “This is for your memory, Dave,” held the

bowl out over the water, and began gently sprinkling out the ashes. As

the boat slowly drifted along, a beautiful line of sinking ashes

stretched out beside it.

|

I set the bowl on the seat board and read the Upanishad, feeling like I did a brave job of it. |

As I emptied the bowl and brought it

back toward me, the guide kindly suggested that the vessel must go,

too. I appreciated the wisdom in this. I dipped the bowl beneath the

water and watched it tumble away, briefly reflecting the morning light,

then did the same with the lid. They looked bright and pretty held

beneath the clear surface, and then faded from view. As the

boat slowly drifted along, a beautiful line of sinking ashes stretched

out beside it.

I took the card and read the committal

blessing I had chosen from the Book of Common Prayer. Jenny had wept

while I read the Upanishad and sprinkled the ashes. I choked up a

little when I got to the part in the blessing, “The Lord bless him and

keep him; the Lord make his face to shine upon him…”

When I finished, the guide explained

that it would be appropriate for us to dip our hands in the water and

fling some

up so it would fall on us as a blessing, so we did, the guide included.

It felt right. As we

were being rowed back toward Shivala Ghat to drop off the boy, he asked

about whose ashes, how I found the text, etc.

The moment the sun appeared above the

horizon, the boatman let go of the oars and bid namasté to it. I

thought he must be a devout Hindu; he had a streak of deep yellow tikka on his forehead, and seemed

genuinely interested in what we were doing. He had a cropped, white

beard and a gentle countenance. He worked hard rowing that boat, too.

No sooner had we gotten underway than

he had shed the white shawl wrapped around his head and body against

the chill. He was clearly poor, and the guide seemed pleased that at

the end of the journey I had given him twenty rupees as baksheesh. He

remarked on the man’s poverty and said that kind of direct remuneration

was a good thing.

As we were rowed on back, what should

appear but a larger boat with that familiar tour group aboard it! They

laughed and the Irish guy called out, “Will you stop stalking me?” I

said I could not help it, I was obsessed.

After the boy disembarked and the

boatman had gone ashore for a moment, we set off again to see more of

the ghats. We were rowed south, all the way to Assi Ghat, then turned

about

and headed back. Along the way, the guide told, among other things, the

myth of the origin of the Ganges, involving water from Shiva twirling

his untied hair round and round (if I understand correctly). We took

pictures of the ghats along the way.

XVII - Doon Express en route to Gaya

The train to Gaya finally arrived over six hours late, departing with

us aboard five minutes before it was originally scheduled to arrive at

our destination. Now, instead of 10:25 p.m., it looks more like well

after 4:00 a.m. Jenny says you cannot have an adventure trip without a

really late train. The Mongolian monk from the U.S. happened by and

suggested in superb American English that the train was just providing

us with an exercise in patience.

While we languished on the platform, I got up the courage to try some sweet paan. The paan-wallah spread various pastes on the betel leaf, added a variety of unusual-looking ingredients to the chunks of betel nut, shaking in other mystery ingredients from little cylindrical tins before folding it all up. I think it is okay to swallow when you chew the stuff, but I was not courageous enough not to treat it like chewing tobacco. Indian men certainly spit a lot with it.

The pieces of betel nut were woody in

texture until they began to soften and chew a little, and the whole

thing had a kind of mild camphor-like taste without being fumy. I

walked along the platform chewing it and spitting between train cars. I

swallowed a little, but it did not seem to have much of any effect. It

is supposed to be mildly narcotic. With hindsight I think all that

spitting was probably unnecessary. I finally got bored with it and spat

it all out. At least my curiosity is satisfied. I bought some bananas

and we ate some on the platform.

Back to the ghats this morning. When we

got back to where we had started, the guide got off and let us continue

alone with the boatman to the northernmost ghats and back. It was a

long trip. He

worked hard rowing that boat.

We passed Harischandra Ghat again, and I noted the modern crematorium

the guide had indicated before. I told him traditional Indian

cremation would be illegal in the U.S.; Jenny said we have fairly

strict laws about handling of the dead. He said the electric

crematorium was only for those too poor to afford a wood fire cremation.

Further north, we came toward Dasaswamedh Ghat where we had begun our walk the day before, with all the brightly painted structures around it. We also came to Manikarnika Ghat where we had watched the cremations. They did not appear to have started for the day.

The rest of the journey was long and

taxing. There were groups of men

having morning baths and socializing; there were men bathing and making

repetitive chants; there were dobi-wallahs swinging wet laundry around

and beating it on stone slabs; there were holy men sitting on the ghats

meditating in the morning sun. At one spot there was a young holy man

sitting in a balcony above the ghat chanting aloud. His lone song

carried out over the water with no electric amplification. Further

north, we came toward Dasaswamedh Ghat, with the brightly painted

structures around it.

During the trip back I was ready to be done and anticipating the return

to shore well before we arrived. I kept thinking our stop was coming up

soon. Back at Shivala Ghat, when the guide suggested a tour of the old

city, I told him we were ready to go have breakfast.

The guide had us climb into cycle-rickshaws and we set off through where Jenny and I had gone the day before. I assumed we would be conveyed to where the auto-rickshaws were waiting at the edge of the old city. After we passed that spot I realized what was happening. Cycle-rickshaws all the way back to the hotel! At least sqeezed in with Jenny and raised up to the morning sun I was beginning to get warm.

At some point during the leisurely if

bumpy poke-along, the cyclist got separated from his colleague ahead,

who was carrying the guide. Then the chain came off the sprockets. It

turned out upon successful return of chain to sprockets after multiple

tries, we went up another street for a block or so and were at the

hotel.

|

There were dobi-wallahs swinging wet laundry around and beating it on stone slabs. |

XVIII

- Room 205, Hotel Tathagat, Bodhgaya, Bihar

(continued)

Back at the hotel we ate breakfast (mine was a good Indian one),

packed, checked out, and stowed the bags with the hotel. We sat down

in the lobby to decide what to do. I would go to the rooftop garden to

write, while Jenny went to get some red tikka powder. She set off. The warm

sun was coming through the front windows of the hotel and it felt good

to sit there. I thumbed through a copy of the Hindustan Times and worked on the

day’s Sudoku puzzle a bit before heading to the rooftop.

It was lovely sitting in the warm sun

with that very pleasant roof garden café all to myself. The time

flew by, and Jenny did not come up to meet me by the time we had

agreed. We had to get to the train station. Little did we know the

train would be six hours late.

|

It was

lovely sitting in the warm sun with that very pleasant roof garden

café all to myself. |

|

Descending the stairs I met Jenny

coming up. She had a woven string of saffron yarn tied around her neck

in good Hindu fashion and a two-inch long smudge of yellow and orange

tikka down the middle of her brow. She had bought her red tikka powder, four such neck

strings for herself and the family, and had gone to see a guru to get

them blessed. He had performed an elaborate ritual over her so she

could be the bearer of the strings’ blessings for the rest of us.

The strings are associated with Shiva

the Destroyer, so all the bad stuff that comes our way will sort of

head for the strings, instead. That seems practical, talismanically

speaking. She said it was fun, and the only time she felt uncomfortable

was when he had to stick a bundle of peacock feathers in her navel. But

she said he was otherwise a nice guy.

Not wearing her watch during this trip,

Jenny did not know how late it had become, but we were still okay. We

got the bags and took an auto-rickshaw to the train station.

We needed a snack to take along, but

there was nothing being sold outside the station except paan, Ayurvedic

medicine and shoeshines. I found a signboard painted in English with

the platform numbers of all the trains through Varanasi, including the

one we were taking. Along the platform there were urchins, disabled

people and old

women begging. We found some empty seats and sat down for what we

thought would be a short afternoon wait, not knowing it would hold the

experiences described above. I did manage to buy those bananas for us.

We were pretty beat when we finally

boarded the train. There was a father with two grown sons who boarded

with us and sat in the same berth across from us. There was a young

blind man sitting there who was apparently in the wrong place, and the

younger men spoke to him in an unkind manner and then laughed about it

as he was leaving. They all took their time eating the meal they had

brought along and rubbing herbal medicine in their palms, but we

finally converted the seat backs to middle berths and turned in.

I wrote for a long while. The train was

dark and dusty and cold, and the elder of the two sons, across from me

on the lower berth, snored like a chain saw. The passenger in the very

top berth got off at some point, so I moved up there, above Jenny and

wrote some more, taking the camera bag with me. I finally set the alarm

and managed to sleep for an hour or so. Jenny woke before I did, and

was a little worried to find the camera bag and me missing from where

we were supposed to be.

XIX - Outside table,

Om Restaurant, Bodhgaya, Bihar

Well, we did finally arrive in Gaya, and slogged out of the darkened

station about 4:30 a.m. We kept telling auto-rickshaw touts, “We have a

car waiting.” They seemed to react with disbelief. I was sort of

following Jenny, who seemed to know where she wanted to go.

The hotel was called Hotel Tathagat.

Jenny

walked right up to a large, white, enclosed jeep with “TATHAGAT” across

the top of the windshield in block letters. Two young men jumped out

and started taking the bags for us. I doubt they had waited the entire

time, but they had been doing some serious smoking inside that car.

Now, we have gone dodging and careening

about in all manner of motor transport in all kinds of places, but this

tended toward the memorable end of the spectrum. Even though it was

such an early hour, there were a lot of very large transport trucks

with blazing headlamps on the narrow, shoulder-less highway. The road

was barely wide enough for two of these to pass, and it was fairly

uncomfortable passing one even in the jeep.

A tape of a female Indian singer blared

in the cab. The driver would run right up on the back of a

cycle-rickshaw or auto-rickshaw and then careen out to pass without

slowing. As long as there was time enough to shoot the gap without

going head-on with a speeding, glaring transport, our rather impressive

speed was seldom reduced.

Jenny was nodding drowsily, and I

thought how her torpor at such a time was something of a blessing. When

your auto-rickshaw is the biggest chicken in the game, it is no big

deal, but with these vehicles the stakes were higher.

The hotel staff alternately wished us

good night and good morning, depending on their grasp of our situation.

The room was as expected, and falling into the otherwise comparatively

hard beds was a welcome experience. We slept from about 5:00 to 10:30

a.m.

After a hot shower (geysers are the

best!) we went next door to the mostly outdoor Om Restaurant, sat in

one of the long rows of umbrella tables in the paved plaza set back

from the dusty, ditchy road, and had some lunch. It was the first

decent food we had eaten in twenty-four hours, and we ate a lot.

Tellingly, there were Chinese, Japanese, European, Indian and Tibetan

selections on the menu.

In addition to various beggars, there

were Buddhist monks and nuns in all combinations of skin and robe

colors, passing by and sitting to relax or eat. There seemed to be a

preponderance of Tibetan monks, and we would soon find out why.

There is a kind of paved court outside

the Mahabodhi Temple with vendor stalls and spreads selling all manner

of religious articles. The large gateway to that area is at one end,

near the front corner of the complex. Vendors spilled around the

gateway and along the road for fifty meters or so, back to the area of

the hotel.

Inside the gateway are places to pay a

camera tax and

check one’s shoes. After we dispatched those items of business, we

noticed that people were lining up along wide stripes of white marble

in the pavement on either side of a path running to the gate of the

temple proper. There was a red carpet rolled out the length of the path.

Many of the people lining up were

Tibetan monks of all ages, but there were also laypeople and

tourists from around the world. We got in line to see the parade. It

was peaceful and orderly. A lot of people were holding a kata (a

small silk prayer shawl that is held in the presence of, or presented

to a lama when he arrives), so we knew it must be someone important.

We chatted with a friendly young woman

from the Irish Republic who informed us that the one arriving was none

other than the Karmapa, who heads a major sect of Tibetan Buddhism

other than the one led by

H.H. the XIV Dalai Lama, and enjoys the latter’s support and approval

over a

poorly received competitor put forward by the Chinese government. How

lucky for us to be there just then!

He is only twenty or so, but tall, lovely, in training since a small

child, and already revered by Tibetan Buddhists everywhere. That

explained the current breakdown of nationalities in town.

We did not have long to wait. Presently

we saw a procession coming and heard the tenor drone of a pair of reed

horns. Someone was carrying a dark red parasol for the Karmapa, and in

front of him was a monk carrying a length of yellow cloth and a kind of

mace similar to a large mala.

They proceeded into the temple proper,

and down the terrace steps into the broad, sunken garden, and we all

followed. The official delegation entered the temple structure and

Karmapa’s voice, amplified into the garden, began chanting. That did

not last long, and soon they all came out and passed by us again.

We went right inside and had a look at

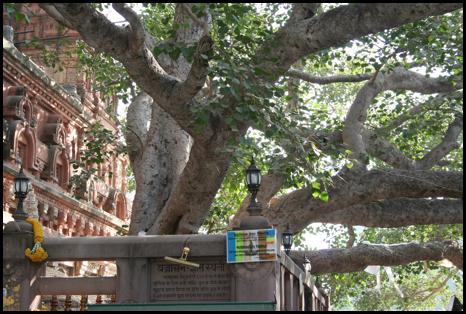

the large golden sitting Buddha, then went around the outside to the

back where the bodhi tree is

located. The building itself forms the

base of a fifty-meter high (about twelve stories) pyramidal stone spire

with a great number of niches built into it. It was covered in

scaffolding, not having had a major restoration since 1882.

The tree out back is growing from a

very large concrete or stone planter box a few feet from the building,

which is surrounded on three sides by ventilated walls abutting the

building and having gold-painted iron gates on either side. The gates

were shut. Inside them, between the planter and the building, is a

richly decorated golden platform and canopy—the Vajrayana, or Diamond

Throne, marking the spot where Siddhartha supposedly sat when he

attained enlightenment.

The walled area sits on a foot-high

platform surrounding the building. Out around the platform is a walk

perhaps another ten feet across, and then a ventilated wall surrounding

the whole on three sides. The platform and walk are paved with gray

marble.

|