Peter Hulen

Peter

and Jenny Hulen, Dave's brother and sister-in-law, traveled to India in

late December and early January 2005-2006 to celebrate their 20th

anniversary. They carried a portion of Dave's ashes to scatter in the

Ganges River, and at the Mahabodhi Temple, site of the bodhi tree under which Siddhartha

Gautama is said to have been sitting when he became enlightened.

Following are excerpts from Peter's Journal relating these experiences

of honoring Dave's memory.

Saturday 31 December 2005:

From the hotel in New Delhi we set out on foot to the Janpath market,

which seems

largely dedicated to Tibetan crafts. It was such a pleasant

late-afternoon walk. At the market I

bought a small, heavy, lidded brass bowl for Dave’s ashes.

Monday 2 January 2006: At

the hotel in Agra I was not feeling well. I lay down

and

thought about details of the committal of Dave’s ashes at

Varanasi and Bodhgaya. As I thought about reading the scriptures and

prayers we had prepared, I began to cry. I felt better after a while,

both emotionally and physically, so I went out to the hotel garden to

sit and

write.

Wednesday 4 January 2006: In

Varanasi we took a pedal-rickshaw through the old city to the edge of

the ghats along the Ganges River. We alit at the end of a

lane at

the top

of

Dasaswamedh Ghat. The last vendor in the lane was a woman selling

beauty notions. Jenny bought a couple of cards of bindhi from her (tiny,

adhesive, jewel-like forehead decorations),

and

she adorned Jenny’s forehead and hairline with spots of deep red tikka

powder. A spot at the hairline (a line in the part, if the hair is

parted) indicates a married woman.

We walked down the long, long

steps of

Dasaswamedh Ghat (it is perhaps thirty or forty yards

wide).

The first thing I noticed to the left was the

huge, orange-painted sikhara

(Hindu spire indicating a temple) at the adjoining ghat to the north.

The ghat we were on opened out wider to the south, below the buildings

facing the river. We strolled in that direction and saw a priest

sitting beneath one of the round, reed-woven umbrellas where they sit.

There were some musicians there, an older man playing a harmonium,

and a younger woman playing tabla

(drums) and singing for all she was worth. We sat down with the others

who were hanging out there and listening.

|

She adorned Jenny’s forehead and hairline with spots of deep red tikka powder. |

As

we sat, we noticed men going

to the

priest (a fairly young one) to be blessed and have marks painted on

their foreheads, after which they made a small donation. Jenny

encouraged me to participate (she was right—when would such a chance

come again?), but I was resistant. As we sat there, I decided on my own

to risk making a fool of myself in exchange for an experience I would

not forget.

I

ventured to the platform

and

under

the umbrella. The priest was peaceful and welcoming with his smile, and

the singing, drumming woman was clearly pleased. I had seen a couple of

different types of applications, and when the priest gestured, asking

if I wanted tilak (a kind of

three-stripe pattern painted clear across the foreheads of devout Hindu

men), I indicated “no” and made a gesture for “little.” He understood,

and I squatted down. He dipped his finger in some deep orange liquid tikka, followed by some intense

yellow. He touched my forehead with it and held it there while he

chanted quietly. It certainly had a blessed feeling to it. He offered a

mirror. The result on my forehead was a deep orange, finger-sized spot

rimmed in yellow.

I

bid him namasté and

gave him a few

rupees baksheesh, and also

the musicians. The woman laughed delightedly, made a beckoning motion

with her fingers and teased, “More!” so I obliged. As we walked back

the other way I remarked to Jenny, either it was a blessing or he sent

me back as a dog, and we chuckled.

|

The

priest was peaceful and welcoming with his smile, and the singing,

drumming woman was clearly pleased. |

|

That afternoon after the ghats, I asked at the hotel front desk about buying offering candles to float on the Ganges, and the best time to start a pre-dawn boat trip, explaining our intentions in addition to a tour of the ghats from the river. A tour guide with the hotel set it all up for us.

Thursday 5 January 2006: During the precious snooze of the travel alarm, the phone rang with the wake-up call the guide had promised, even though we had told him not to bother. When we found him in the lobby wearing a down coat and furry hat, I thought my fleece vest might not be enough. Confirmation came when we stepped outside. Jenny waited while I ran up to get more layers. It was chilly, but we were okay. The guide slipped in next to the driver of the auto-rickshaw.

We put in at Shivala Ghat, quite away south of the ghats we had been at the day before. The boatman rowed northward three or four ghats until we were opposite Harischandra Ghat and a little way out from shore. We stopped there, as arranged.

When we had

walked down Shivala

Ghat

toward the boat, we were met by a cheerful little boy in an open-faced

ski mask with a basket of the candles we had asked about—about a dozen

of them. We bought the lot from him and he accompanied us out onto the

boat to assist, carrying the basket of votives with him. The guide had

been sweetly affectionate with him, tweaking his cheeks and patting his

head. They

were in your memory, Dave.

Harischandra is one of the oldest of all the ghats in this, one of the

oldest cities in the world; Varanasi dates from two millennia BCE.

Harischandra is also a cremation ghat, and the wood was stacked as at

Manikarnika Ghat. It was also stacked high in boats moored at the ghat.

The votives each consisted of a

small

bowl shaped much as a small, paper picnic bowl would be, except molded

of some kind of broad, brownish-green, dry leaves (betel leaves, I

think).

Each bowl served as a little boat. In the center was something

like a tea candle, surrounded by a ring of marigold blossoms.

When we boarded the boat, the

little boy began taking something soft and white from a small plastic

container and forming it around each wick. I have no idea what it was

(yak butter is a possibility), but perhaps it fueled the wicks in the

breeze until the

wax began to melt and wick to the flame. He began lighting them, until

the guide explained that we would be putting them into the river

elsewhere.

When we stopped opposite

Harischandra

Ghat, the boy began lighting the candles and handing them to Jenny and

me, and we, in turn, laid them on the water. They floated away behind

us and Jenny took photos. They were in your memory, Dave.

I took the cardstock with a

scripture

from the Upanishads and a blessing from

the Book of Common Prayer printed on it out of the yarn bag I bought

from Uighurs in China; and, I also

brought out the lidded brass bowl from the Janpath market in Delhi, now

containing half the portion of Dave’s ashes we had brought along. As we

untied the piece of selvage holding on the lid, the guide commented

admiringly on the bowl. I set it on the seat

board and read the

Upanishad aloud, feeling like I did a brave job of it.

“All

this is inhabited by God, whatever that moves here in this moving

universe. Unmoving, yet swifter than mind, beyond the reach of the

senses and always ahead of them; standing, it outruns those who run. In

it, the all-pervading presence supports the activity of all beings. It

moves and it moves not. It is far and it is near. It is inside all this

and also outside all this. The one who sees all beings in his own self

and his own self in all beings does not suffer from any repulsion by

that experience. The one who has known that all beings have become one

with his own self, and the one who has seen the oneness of existence,

what sorrow and what delusion can overwhelm him? That one has occupied

all. That one is radiant, without body, without injury, without sinew,

pure, untouched by evil. That one is the seer, thinker, all pervading,

self-existent, has distributed various objects, through endless years,

each according to its inherent nature.

“Who

so ever person is there beyond, that also I am. May this breath merge

into the immortal breath. Then may the body end in ashes. OM, remember what has been done, O

intelligence remember what has been done, remember, remember!”

I

picked up the

bowl, removed the lid, said, “This is for your memory, Dave,” held the

bowl out over the water, and began gently sprinkling out the ashes. As

the boat slowly drifted along, a beautiful line of sinking ashes

stretched out beside it.

|

I set the bowl on the seat board and read the Upanishad, feeling like I did a brave job of it. |

As

I emptied

the bowl and

brought it

back toward me, the guide kindly suggested that the vessel must go,

too. I appreciated the wisdom in this. I dipped the bowl beneath the

water and watched it tumble away, briefly reflecting the morning light,

then did the same with the lid. They looked bright and pretty held

beneath the clear surface, and then faded from view. As the

boat slowly drifted along, a beautiful line of sinking ashes stretched

out beside it.

I took the card and read

the

committal

blessing I had chosen from the Book of Common Prayer.

“In

sure and certain hope of resurrection and eternal life we commend to

God our brother Dave, and we commit his body to the elements; earth to

earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The Lord bless him and keep him,

the Lord make his face to shine upon him and be gracious to him, the

Lord lift up his countenance upon him and give him peace. Amen.”

Jenny had wept

while I read the Upanishad and sprinkled the ashes. I choked up a

little when I got to the part in the blessing, “The Lord bless him and

keep him; the Lord make his face to shine upon him…”

When I finished, the guide

explained

that it would be appropriate for us to dip our hands in the water and

fling some

up so it would fall on us as a blessing, so we did, the guide included.

It felt right. As we

were being rowed back toward Shivala Ghat to drop off the boy, the

guide asked

about whose ashes, how I found the text, etc.

The moment the sun appeared above the horizon, the boatman let go of the oars and bid namasté to it. I thought he must be a devout Hindu; he had a streak of deep yellow tikka on his forehead, and seemed genuinely interested in what we were doing. He had a cropped, white beard and a gentle countenance. He worked hard rowing that boat, too.

No

sooner had we gotten

underway

than

he had shed the white shawl wrapped around his head and body against

the chill. He was clearly poor, and the guide seemed pleased that at

the end of the journey I had given him twenty rupees as baksheesh. He

remarked on the man’s poverty and said that kind of direct remuneration

was a good thing. He

worked hard rowing that boat.

Along the way, the guide had told, among other things, the

myth of the origin of the Ganges, involving water from Shiva twirling

his untied hair round and round (if I understand correctly). He also

asked about Dave, so I related Dave’s story to him briefly. I heard him

telling the boatman, making out words borrowed into Hindi from English,

including “accident” and “wheelchair.” The guide said that the boatman,

having watched us, was interested.

Further

north,

we came toward

Dasaswamedh Ghat where we had begun our walk the day before, with all

the brightly painted structures around it. The rest of the journey was

long

and

taxing, but also very meaningful. There were groups of men

having morning baths and socializing; there were men bathing and making

repetitive chants; there were dobi-wallahs swinging wet laundry around

and beating it on stone slabs; there were holy men sitting on the ghats

meditating in the morning sun. At one spot there was a young holy man

sitting in a balcony above the ghat chanting aloud. His lone song

carried out over the water with no electric amplification. Further

north, we came toward Dasaswamedh Ghat, with the brightly painted

structures around it.

|

There were dobi-wallahs swinging wet laundry around and beating it on stone slabs. |

Friday

6 January 2006: By the next day we were sitting at an outdoor

table at the Om Restaurant in Bodhgaya. In addition to various

beggars,

there

were Buddhist monks and nuns in all combinations of skin and robe

colors, passing by and sitting to relax or eat. There seemed to be a

preponderance of Tibetan monks, and we would soon find out why.

There is a kind of paved

court

outside

the Mahabodhi Temple with vendor stalls and spreads selling all manner

of religious articles. The large gateway to that area is at one end,

near the front corner of the complex. Vendors spilled around the

gateway and along the road for fifty meters or so, back to the area of

the hotel.

Inside the gateway are

places to

pay a

camera tax and

check one’s shoes. After we dispatched those items of business, we

noticed that people were lining up along wide stripes of white marble

in the pavement on either side of a path running to the gate of the

temple proper. There was a red carpet rolled out the length of the path.

Many of the people lining

up

were

Tibetan monks of all ages, but there were also laypeople and

tourists from around the world. We got in line to see the parade. It

was peaceful and orderly. A lot of people were holding a kata (a

small silk prayer shawl that is held in the presence of, or presented

to a lama when he arrives), so we knew it must be someone important.

We chatted with a

friendly young

woman

from the Irish Republic who informed us that the one arriving was none

other than the Karmapa, who heads a major sect of Tibetan Buddhism

other than the one led by

H.H. the XIV Dalai Lama, and enjoys the latter’s support and approval

over a

poorly received competitor put forward by the Chinese government. How

lucky for us to be there just then!

He is only twenty or so, but tall, lovely, in training since a small

child, and already revered by Tibetan Buddhists everywhere. That

explained the current breakdown of nationalities in town.

We did not have long to

wait.

Presently

we saw a procession coming and heard the tenor drone of a pair of reed

horns. Someone was carrying a dark red parasol for the Karmapa, and in

front of him was a monk carrying a length of yellow cloth and a kind of

mace similar to a large mala.

They proceeded into the

temple

proper,

and down the terrace steps into the broad, sunken garden, and we all

followed. The official delegation entered the temple structure and

Karmapa’s voice, amplified into the garden, began chanting. That did

not last long, and soon they all came out and passed by us again.

We

went right

inside and

had a

look at

the large golden sitting Buddha, then went around the outside to the

back where the bodhi tree is

located. The building itself forms the

base of a fifty-meter high (about twelve stories) pyramidal stone spire

with a great number of niches built into it. It was covered in

scaffolding, not having had a major restoration since 1882.

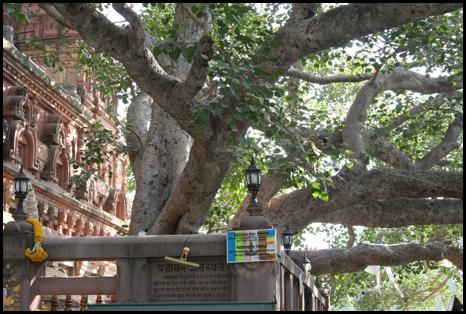

The tree out back is

growing

from a

very large concrete or stone planter box a few feet from the building,

which is surrounded on three sides by ventilated walls abutting the

building and having gold-painted iron gates on either side. The gates

were shut. Inside them, between the planter and the building, is a

richly decorated golden platform and canopy—the Vajrayana, or Diamond

Throne, marking the spot where Siddhartha supposedly sat when he

attained enlightenment.

The

walled area

sits on a

foot-high

platform surrounding the building. Out around the platform is a walk

perhaps another ten feet across, and then a ventilated wall surrounding

the whole on three sides. The platform and walk are paved with gray

marble.

|

Many of the people lining up were Tibetan monks. |

Atop the platform along the north side of the temple is another table-high stone platform with round, lotus-carved stone discs supposedly marking the footsteps of the Buddha where he walked in meditation. Each one was piled with marigold and rose blossoms, and all along was a row of new yak butter candles, each decorated with two large, pastel-colored yak-butter rosettes, along with rice and incense. We followed around that way to find the tree in back.

Looking in at a gate of

the wall

surrounding it, one can see that the trunk is about five or six feet in

diameter. Its massive branches spread out over the wall around the

planter, forming a canopy over the marble walk, and extending over and

far beyond the outer wall of the walk.

There is a marble seat

along the

walk

inside the wall, and sit we did. It was beautiful, peaceful, and very

meaningful. There was a Tibetan woman sitting by one of the gates

spinning a prayer wheel. Facing the other gate was a group

of monks, nuns and laypeople sitting in meditation.

Indian

tourists—clearly

Hindu—were

walking by, some with hands held in an attitude of prayerful respect.

Some would touch the gate or wall around the tree and touch their

forehead or over their heart in blessing. Fascinating. When will a

majority of Christians and Muslims develop that kind of openness?

|

All

along was a row of new yak butter candles, each decorated with two

large, pastel-colored yak-butter rosettes, along with rice and incense.

|

|

The wall surrounding the

tree

was

draped across with a long yellow piece of cloth and multi-colored

prayer flags. At the back there is a window-like opening in the wall

with something like brass balusters just inside it. One can peek

between them and see the trunk and a bit of the earth out of which it

grows. That made me think of what we might do with the rest of Dave’s

ashes.

Jenny and I walked up the

terrace

steps, back up out of the garden, and

strolled along the perimeter walk above the terrace. On the south side

is a grassy area set aside as a meditation garden. Beyond it is a small

lake with a large painted concrete sitting Buddha in the center,

protected from the storm under the cobra-hood of the snake king. I will

forbear writing the whole legend.

There was not a Buddhist in sight. The only people by the water were a large group of Hindus doing a Ganges thing—reaching down and flicking handfuls of water up into the air so it fell on them in blessing. How very interesting.

|

Its massive branches spread out over the wall, forming a canopy over the marble walk. |

That afternoon, besides shopping for a singing bowl among the vendors outside the temple, I was also scanning for something that would work for the rest of Dave’s ashes, trying to be open-minded and creative about what to do. Among the wares spread out on her blanket, one woman had some thin jade rice bowls. I was thinking of something that might smash easily. I moved on so I could think about it some more.

Chai from roadside vendors is sometimes served in what look to me like thin clay bowls. I was thinking something earthen and fragile like that would be good for what I had in mind for Dave’s ashes. That night we went so far as to buy some chai from a man selling food by the roadside, but he served it in “disposable” plastic cups.

We headed back over by the Mahabodhi Temple to look for something that would work. I was seeing little stone bowls, but I was not sure they would break easily. We went back to where the jade bowls had been, but the woman and her wares were gone.

At the court alongside the temple, I looked in a shop that had caught Jenny’s eye. The man asked what I wanted. I explained. He said to come back in the morning and he would have a small clay pot. We decided we could make time to check back and/or look around some more in the morning.

A few shops down, there was a photocopy and IDD place, so we decided to stop and call the kids. It was fun to talk to them. As we were paying for the call, the man from the other shop appeared, beaming, holding a small, hastily washed, round clay pot. Perfect! We bought it from him for what to us was a pittance, and to him was probably a steal on what might have otherwise been considered a piece of junk; but all concerned were happy.

We walked over by the

hotel, the

Om

Restaurant, and other shops. We looked around in a shop with clothes

and tee shirts, me carrying the little pot

along.

Saturday 7 January 2006: The next morning we placed the rest of Dave’s ashes into the little pot. Jenny carried it discreetly under her shawl as we walked to the Mahabodhi Temple. Once inside, she handed it to me and I held it next to me as we began to carry Dave’s ashes above the garden terrace, clockwise around the entire temple.

What a surprise we had in store. It was more right than either of us could have made it. As we began to walk, I chanted over and over slowly and very softly, “Om mani padme hum.” But then we looked down into the garden below and saw that there were hundreds of monks and nuns—they had come to town from everywhere and filled every hotel to see the Karmapa and hear his teaching that evening. A riot of colors from maroon through orange and on to bright yellow. They were all sitting, facing the temple all around.

|

I held

the little pot next to me as we began to carry Dave’s ashes clockwise

around the temple. |

|

As we reached the first corner, about one-eighth of the way around, they all began to chant! Sometimes, sometimes, things work out in such an unexpected way. Jenny remarked that it was not our karma that brought all this together, but Dave’s.

We

slowly

walked all the

way

around

carrying Dave’s ashes, and the monks and nuns chanted the entire time.

They continued as we descended the terrace steps and went around again

on the walk below the terrace at the perimeter of the garden. Finally,

we went into the center and started on the walk around the great stone

spire of the temple itself. At that point, all the monks and nuns were

facing us and the sound was amazing. There were hundreds of monks and nuns.

The second time around we stopped at the tree. Jenny took the pot,

extended it through the window-like opening in the back wall, between

the brass balusters, and flung the ashes at the base of the tree, the

chanting continuing all the while.

We

carried the

empty pot

to a

spot I

had chosen at the northeast corner of the garden. I raised it and

smashed it on the base of an old stupa, then gently pounded the largest

shards into smaller. We started around the garden one more time, and I

flung the little potsherds into the garden as we slowly walked. Jenny

extended the pot between the brass balusters, and flung the ashes at

the base of the tree, the chanting continuing all the while.

It would not be right to omit the next part. About one-fourth of the

way around again, I really, really needed to go to the bathroom. Jenny

said she would wait. We both stepped out the gate and Jenny sat down.

The monks finished chanting as we exited. Jenny took the handful of

potsherds and I walked on out, grabbed my boots (they had been Dave’s

boots), headed the block or so back to the hotel, and returned as

quickly as I could. No sooner had we walked back into the temple than

the chanting started again!

We

walked on around with

me

flinging

the little potsherds. Jenny took some and did the same. When we got

back around to the stupa where I had smashed the little pot, I pulled

out the card with the sutras and committal blessing I had prepared to

read. For some reason, it just did not feel right to read them out

loud, so we stood still and I read them silently as Jenny stood near.

“Let

go of the past! Let go of the future! In the present, let go! Gone to

the other shore of becoming, mind released entirely, you will never

again undergo birth and old age. The person who has traversed this

difficult, muddy path—the bewilderment that is the swirl of

becoming—the meditator who has crossed over, reached the other shore,

free from desire, free from doubt, not grasping, unbound, that one I

call superior.

“Therefore,

O Sariputra, in emptiness there is no form, nor feeling, nor

perception, nor impulse, nor consciousness; No eye, ear, nose, tongue,

body, mind; No forms, sounds, smells, tastes, touchables or objects of

mind; No sight-organ element, and so on, until we come to: no

mind-conscious element; There is no ignorance, no extinction of

ignorance, and so on, until we come to: no decay and death. There is no

suffering, no origination, no stopping, no path. There is no cognition,

no attainment and no non-attainment.

“What do you

think,

Subhuti, is Tathagata to be seen through the attainment of his

physical-form body? Subhuti replied: No indeed, O Lord, Tathagata is

not to be seen through the attainment of his physical-form body. And

why? ‘Attainment of his physical-form body, attainment of his

physical-form body,’ this, O Lord, has been taught by Tathagata as

non-attainment; so it is called ‘attainment of his physical-form body.’

“What you sow

does

not come to life unless it dies. And as for what you sow, you do not

sow the body that is to be, but a bare seed, perhaps of wheat or of

some other grain. But then God gives it a body as he has chosen, and to

each kind of seed its own body. So it is with the resurrection of the

dead. What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable. It is

sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is

raised in power. It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual

body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body. Thus

it is written, ‘The first man, Adam, became a living being’; the last

Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual that is

first, but the physical, and then the spiritual. The first man was from

the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven. As was the man

of dust, so are those who are of the dust; and as is the man of heaven,

so are those who are of heaven. Just as we have borne the image of the

man of dust, we will also bear the image of the man of heaven.

“Lord Jesus

Christ,

we commend to you our brother Dave, who was reborn by water and the

Spirit. Grant that his death may recall to us your victory over death,

and be an occasion for us to renew our trust in your love. Give us, we

pray, the faith to follow where you have led the way; where you live

and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, for all ages. Amen.”

|

|

I flung the little potsherds into the garden as we slowly walked. |

It

felt

good for everything to have worked out so well.

I hope the

committal of

some of Dave's ashes at these two holy places and

the excerpts from my journal about these acts of loving remembrance

will continue to be a comfort to all of us who knew and loved Dave.

31 December 2006